Patellar Luxation in Small Breed Dogs

by Teri Dickinson, DVM

Luxated patellas or "slipped stifles" are a common orthopedic problem

in small dogs. A study of 542 affected individuals revealed that dogs

classified as small (adult weight 9 kg (20 lbs) or less) were twelve

times as likely to be affected as medium, large or giant breed dogs.(1)

In addition, females were 1.5 times as likely to be affected.1

Some researchers have suggested a recessive method of inheritance,(2),(3)

and the higher incidence in females could possibly be related to

X-linked(4) factors or hormonal

influences.

Luxated patellas are a congenital8 (present at birth)

condition. The actual luxation may not be present at birth, but the

structural changes which lead to luxation are present. Most researchers

believe luxated patellas to be heritable (inherited) as well, though the

exact mode of inheritance is not known. The condition is commonly seen

in Italian Greyhounds, although no published data regarding the

incidence in IG's exists at this time. Researchers1 have

suggested that due to the high risk factor in toy breeds, breeding

trials or retrospective pedigree analyses should be undertaken by

national breed clubs to answer some of these questions.

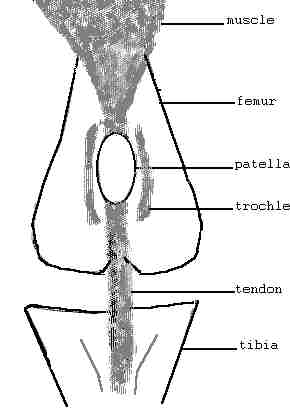

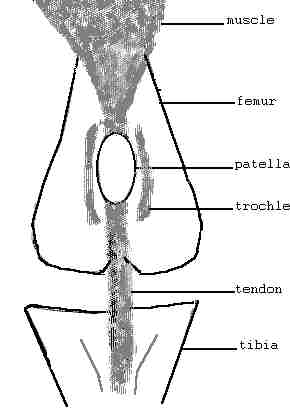

The

stifle is a complicated joint(5) which is

the anatomical equivalent of the human knee. The three major components

involved in luxating patellas are the femur (thigh bone), patella (knee

cap), and tibia (calf or second thigh). See drawing A. In a normal

stifle, the femur and tibia are lined up so that the patella rests in a

groove (trochlea) on the femur, and its attachment (the patellar tendon)

is on the tibia directly below the trochlea. The

stifle is a complicated joint(5) which is

the anatomical equivalent of the human knee. The three major components

involved in luxating patellas are the femur (thigh bone), patella (knee

cap), and tibia (calf or second thigh). See drawing A. In a normal

stifle, the femur and tibia are lined up so that the patella rests in a

groove (trochlea) on the femur, and its attachment (the patellar tendon)

is on the tibia directly below the trochlea.

The function of the patella is to protect the large tendon of the

quadriceps (thigh) muscle as it rides over the front of the femur while

the quadriceps is used to extend (straighten) the stifle joint. Placing

your hand on your patella (knee cap) while flexing and extending your

stifle (knee) will allow you to feel the normal movement of the patella

as it glides up and down in the trochlea.

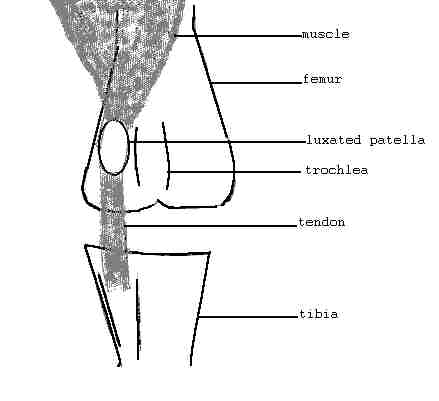

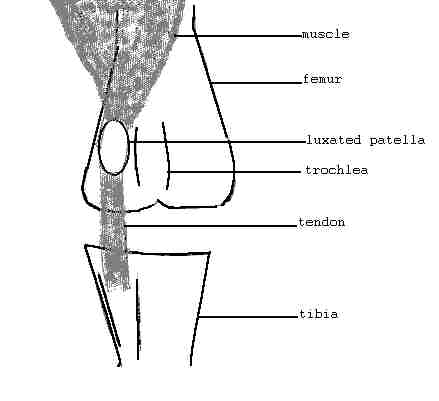

Luxation

(dislocation) of the patella occurs when these structures are not in

proper alignment.(6) Luxation in toy

breeds most frequently occurs medially (to the inside of the leg). See

drawing B. The tibia is rotated medially (inward) which allows the

patella to luxate (slip out of its groove) and ride on the inner surface

of the femur. Luxation

(dislocation) of the patella occurs when these structures are not in

proper alignment.(6) Luxation in toy

breeds most frequently occurs medially (to the inside of the leg). See

drawing B. The tibia is rotated medially (inward) which allows the

patella to luxate (slip out of its groove) and ride on the inner surface

of the femur.

While the patella is luxated, the quadriceps is unable to properly

extend the stifle, resulting in an abnormal gait or lameness. In

addition, the smooth surface of the patella is damaged by contact with

the femur, rather than the smooth articular (joint) cartilage present in

the trochlea. With time this rubbing will result in degenerative joint

disease (arthritis). Furthermore, while the patella is luxated, the

quadriceps puts a rotational force on the tibia, which over time will

increase the rotation of the tibia, thereby increasing the severity of

the problem. The additional strain caused by the malformation of the

bones may also lead to later ligament ruptures. Many individuals are

affected bilaterally (both legs).

Signs of luxation may appear as early as weaning or may go undetected

until later in life. Signs include intermittent rear leg lameness, often

shifting from one leg to the other, and an inability to fully extend the

stifle. The leg may carried for variable periods of time. Early in the

course of the disease, or in mildly affected animals, a hopping or

skipping action occurs. This is due to the patella luxating while the

dog is moving and by giving an extra hop or skip the dog extends its

stifle and is often able to replace the patella until the next luxation,

when the cycle repeats.

Several grades of luxation have been defined(7),5.

In simple terms they are:

- Grade I. Patella can be luxated manually (by the examiner) but

returns to the trochlea when released. Occasional luxation occurs

causing the animal to temporarily carry the limb. Tibial rotation is

minimal

- Grade II. Patella can be easily luxated manually and remains

luxated until replaced. Luxation occurs frequently for longer

periods of time, causing the leg to be carried or used without full

extension. Tibial rotation is present.

- Grade III. The patella is permanently luxated, but can be

replaced manually. The dog often uses the leg, but without full

extension. Tibial rotation is marked.

- Grade IV. The patella cannot be replaced manually, and the leg

is carried or used in a crouching position. Extension of the stifle

is virtually impossible. Tibial rotation is quite severe, resulting

in a "bow legged" appearance.

While no data has been published, personal observation reveals most

affected IG's appear to have Grade I or II luxations. I have also

encountered puppies born with no trochlea and severe tibial rotation

causing permanent luxation from birth (Grade IV), and adult dogs so

severely affected they were non-weight bearing in both hind legs and

merely dragged their rear legs along in a frog-like position (Grade IV).

Diagnosis is relatively simple for a veterinarian familiar with

orthopedics. It involves palpation of the joint and manual luxation of

the patella. X-rays may also be used to determine the degree of

rotation. Motivated owners may be trained by veterinarians to palpate

the stifles, but care must be exercised in order to avoid injuring the

joint, or making an incorrect diagnosis.

Diagnosis in severe cases may be possible at weaning, but in most cases

the joints should be tight enough at 4 to 6 months(8)

to allow reliable palpation. Screening of puppies at this age will help

prevent large expenditures training and showing dogs which later prove

unsound. Screening of breeding stock and culling of affected individuals

should, over time, reduce the incidence of the condition.

Treatment involves surgical correction of the deformities. Many

techniques are available depending on the severity of the condition.(9)

Satisfactory results are usually obtained if the joint degeneration has

not progressed too far. Once the condition is repaired, most affected

individuals make satisfactory pets.

Bibliography

1. Priester WA: Sex, Size and Breed as Risk

Factors in Canine Patellar Luxation. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 160:740, 1972.

2. Hutt FB: Genetic Defects of Bones and Joints in

Domestic Animals. Cornell Vet. 58:104, 1968.

3. Kodituwakku GE: Luxation of the Patella in the

Dog. Vet. Rec. 74:1499, 1962.

4. present on the X chromosome, of which females

have two, XX and males one, XY

5. Miller, ME: Anatomy of the Dog. WB Saunders

Co., Philadelphia, PA 1964.

6. Putnam RW: Patellar Luxation in the Dog. M.Sc.

Thesis. Presented to the faculty of graduate studies, University of

Guelph, Ontario, Canada, January 1968.

7. Singleton WB: The Surgical Correction of Stifle

Deformities in the Dog. J Small An Pract 10:59, 1969.

8. Archibald J: Canine Surgery. American

Veterinary Publications, Santa Barbara, CA, 1974.

9. Brinker WO: Handbook of Small Animal

Orthopedics & Fracture Treatment. WB Saunders Co., Philadelphia, PA,

1990.

|

The

stifle is a complicated joint

The

stifle is a complicated joint Luxation

(dislocation) of the patella occurs when these structures are not in

proper alignment.

Luxation

(dislocation) of the patella occurs when these structures are not in

proper alignment.